-

1. Meeting UNION

-

2. Architecture and Aspiration

-

3. Details in Japanese Architecture

-

4. The Lasting Beauty of Quality Materials

-

5. Self-Expectations and Achievements

-

6. Structure, Design and Innovation for the Coming Generation

-

7. A Wide View for the Global Market

-

8. What the UNION Foundation of Ergodesign Culture Achieved

-

9. Conceptual Products that Cross Borders

1. Meeting UNION

It’s good to have you with us again today.

You and us at UNION go back a long time.

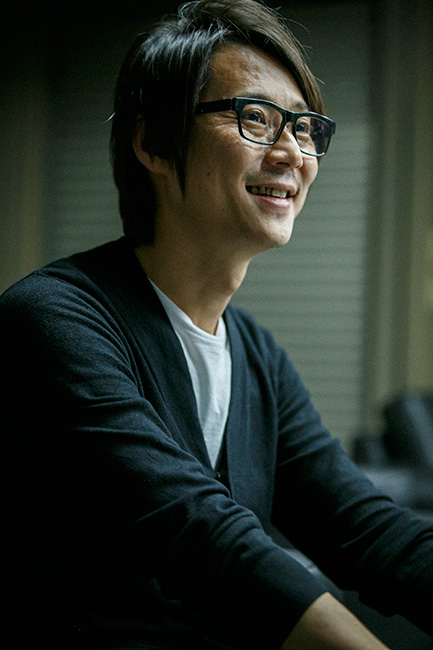

Yes, since I was about 20. So it’s been about 25 years *Laughs.*

Has it been that long? It all started with Takehara didn't it?

Yes, at that time, I think he was the department chief, after that he went on to become managing director.

You were a student back then. Was there a reason that you and Takehara became close then?

I was born in 1971 and had turned 18 in 1989. It was just at the climax of the economic bubble. The construction bubble burst a little later. The construction industry was booming so much that they couldn't find enough hands to help. I was going to university at night, at the time we were called “working students.” I worked at an architectural firm during the day. From spring of my first year in university, I began to spend my days in the office and my nights in school. In the summer of my 3rd year, the firm I was working at told me to take the exam for my architectural license. I took it and somehow passed. At that time, if you had passed the exam, a lot of architectural firms would let you join the Architects Association. After I had joined, I was told to take part in the Architects Association golf tournament. Takehara happened to be giving a presentation at the same party, and we got acquainted.

Had you played golf before?

Yes. *Laughs.* From early elementary school until entering high school I wanted to be a pro surfer. Just around the time I gave up surfing because of a sea accident, my cousin was playing golf at university. He taught me how to play one day, and because of that I joined the high school golf team.

Really! I didn't know you could golf. Where did you play?

At the Sakai country club. I think it's the closest golf course to Osaka. I practiced golf there while working part time. In the beginning I went there by bus when I didn't have school, then as a sophomore, I got a job picking up balls. I went there by motorbike early every morning. From spring to summer, the sun would rise early and I could fit in a round or two before opening. Most of the people working part time in the morning were members of their university's or work's golf teams. Lots of them were aiming to go pro. I was young and playing golf with these people every day, so I improved very quickly. In those days golf was a marker of the successful. I think part of the reason Takehara-san took an interest in me is because I was young and played golf. Just at that time, Noi-san, master of interior design, was making a showroom for UNION. Takehara-san invited me to have a look with him. That space made a strong impression on me.

That space was originally our product warehouse. We had just moved the warehouse to Higashi Osaka and I was wondering what to do with the space. After we decided to make it into a showroom, we got Shigemasa Noi to design it. It was very cutting edge at the time.

That’s true. In those days, because they were notoriously difficult to maintain and keep clean, white cube designs were rare, so I was really looking forward to meeting Takehara-san in the showroom.

Didn’t he take you to see a bunch of other projects, too?

Yes, he took me to see some of the things UNION was doing at the time. He also took me to see Takenaka construction and Obayashi Gumi construction, as well as the design departments of most of the representative general construction firms in Osaka. Then there were places like Sakura Associates and Yasui Architects & Engineers, who were a force in Kansai at the time. And, of course, he also took me out drinking more than once. *Laughs.* We went to some really amazing avant-garde places.

The construction world was really booming. There were so many great designers, builders and craftsmen in Kansai then. Of course, there were many strange and interesting places to go drinking, too.

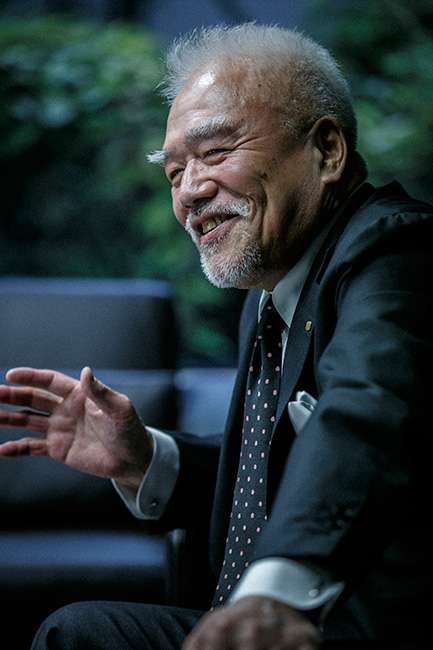

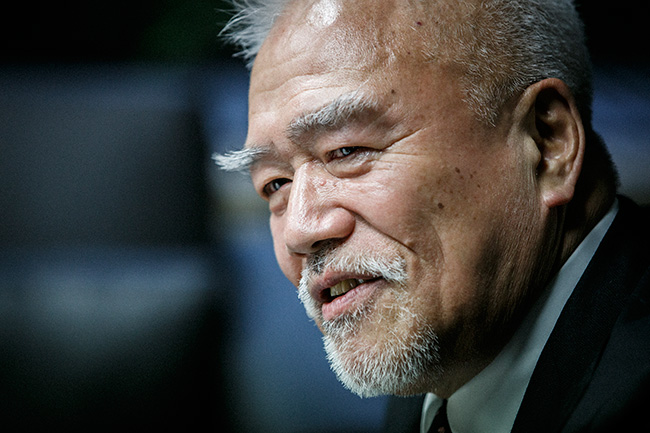

Didn't you become company president around that time?

This year will be my 27th, so… yeah, I guess I did! That was such a great time, although the economy started to go into a worsening slump then. At the time, you were studying at night school and working at an architectural firm but were still able to go and study at the AA school in England, right?

Yes. While I studied abroad, I got to take part in many different building projects. I think keeping my place at the architectural firm during that time was the ideal way to go about it, so in that respect I was lucky. One of the many times I came back to Osaka, I got the chance to drink with you. I remember it being the first time we really had a chance to talk.

That’s right, at that time I was meeting with lots young people. Mentoring and sponsoring them, basically. *Laughs.*

I'm not sure how to describe you back then. You understood how to guide us budding architects. You supported us in exploring our ideas on design, and gave us many new ones. But more than anything else, you always challenged us.

Maybe so. But you've been helping to mentor a younger generation for a while now. I really respect that. It's an important role that not just anyone can fill.

It's because you looked after us when we were young; you helped us grow as architects. I'm grateful for the support I received, which motivated me to do something for the next generation.

I guess so, but it's something that's really difficult to continue doing. Now it's really hard to make a living in our field. The older generation of designers is living and working for longer, which means opportunities for the young are few and far between. It's really difficult for people to make ends meet working only domestically. Everyone who succeeds goes abroad, like you.

2. Architecture and Aspiration

Recently, more general construction firms are also designing the architecture of the buildings they make. I guess the customers probably think it's more efficient that way. What's your view on this?

Our role as architects is to understand the context of the area we are building in, and to apply that knowledge in a way that befits the surroundings. To build within and around historical considerations, as well as those of environment, composition, finishing and details, all the way through suggestions on function. We also must consider who is intended to use the space we design. After a building is complete, we have to consider how the building will serve the community and city it’s in. We also think about the culture it will become a part of and ask how it can continue to be useful. At the same time, we have a responsibility to represent our clients. When working with those who have little knowledge of architecture, we research relevant laws and building codes and apply for all necessary building permits in their stead. Then we draw up plans that reflect all this. We create plans that double as construction guidelines and economic and logistical projections. On top of that, we have to evaluate and hire contractors based on their material procurement routes and the quality of their employees. Another of our roles is to provide temporary construction plans and blueprints during the construction phase and to ensure the theoretical designs align with the actual building site. Basically, I think an architect plays three roles in one: a designer, an adviser and representative of the client, and a manager of various sub-contractors and builders.

That's right. Design involves repeated negotiations and discussions confirming that the functions, materials, and all sorts of details written into the plans are being properly executed at the worksite. A successful architect acts as the eyes and ears of his or her client. Supervision and management are both vital. Maybe I shouldn't say this, but if design and construction are done by the same company corners get cut. Everyone involved is accountable to the same set of corporate demands.

I agree. Clients need architects who can competently represent them, legally and otherwise. About 10 years ago I was asked to design for the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Industrial Science campus. They have a building called the University of Tokyo Laboratory building. My client was Professor Maeda, who later became Vice Dean of Tokyo University. He said to me “the main job of the client is to create a budget for the project in consultation with an architect. And the most fun job of the client is choosing the architect."

The Japanese construction industry is excellent. With general contractors above a certain level, we can make high quality buildings. But if one company is asked to do both design and construction, then the design becomes budget minus profit. All the motivation shifts to just finishing building something.

Yes, buildings are built with a mindset of avoiding liability and doing the minimum possible. I think it's the same in any kind of manufacturing. I want the end user to feel appreciation for the great beauty or the charm of a building, and to cherish it. You have to create with that mindset. Nowadays, the focus is on the profits and ease of building; nobody looks at the architecture.

Nowadays wherever you look all you see is the same kind of building. When the number of people who appreciate and demand good architecture decreases, it's bad for the whole industry. When I went to Hong Kong the other day, I thought that the architecture was really interesting. It's an amazingly attractive city.

Each building develops the aesthetics of the city as a whole. If they just threw together buildings for quick profits, then I think they would incur a debt of social and economic costs to be paid off in the future.

Yeah *Laughs.* That’s exactly it. Many of the buildings have parts that appear to float, protruding out in various directions. The asymmetric style is a result of the uneven terrain. You don't really see this with Japanese buildings.

Architecture has to differ, because terrain differs. I want people to feel guilty when they design buildings that look the same as everyone else's. But for some reason, when investors see one financially successful case study, they think they can replicate it in different locations. They repeatedly fail by believing in numbers based on unreliable data! *Laughs.* You can see this with modern department stores. As you were saying, we need to see the values that lie beyond the status quo. We have to turn constraints into opportunities. That's where originality is born.

Exactly. It would be great if there were more young people who thought like that. We need to want to inhabit interesting spaces, to demand to live in them! If that became a mainstream requirement of today’s generation, then we would have no choice but to confront the way everything gets built.

I want cities and their architecture to reflect the desires of people with the courage to build in new directions, people who feel the excitement and joy of the process of creation. Not pre-existing market research.

I think fun and boredom each have a way of expressing themselves in the finished product. It's inevitable that some visions will get restrained by construction budgets and other economic considerations. But I would like to see intentions, desires, and real heart expressed within those constraints. On the flip side, I would love to see that demand made of us manufacturers. It would help to preserve craftsmanship. At the current rate we craftsmen soon won't have the skills to do high-quality work even if we want to.

Basically, as designers we love making beautiful things. It's the foundation of any design, including designing buildings. Rather than installing a bunch of mass-produced things, wherever possible I'd like to reflect the quality of the space with expression born through originality. But initial cost always proves a major problem. And then, because of time constraints, suggesting new products and materials to clients creates concerns about accidents or durability. The high cost of architecture creates a demand for verified products.

That makes sense.

We're living in an age of verification. Whenever anyone wants to create something new, they need to discuss their idea with a specialist who is actually going to make the product. And only if they can really sell the manufacturer on the idea, can they take on the challenge together. In your case, I trust you and your deep cultural understanding to guide me towards new challenges. It's a source of great encouragement! *Laughs.*

*Laughs.*

On the other hand, some clients make requests without a good understanding of the process involved. Then it can be hard on the manufacturer or designer who gets pushed to fulfill impossible requests.

Yeah, sometimes that's just how it goes.

But let's use this experience, and if we can get over this last obstacle, then I believe we can create something special *Laughs.*

Hahaha *Laughs.* I'm expecting great things.

3. Details in Japanese Architecture

I've always thought the ceiling of the Hiten Main Banquet Hall in the Grand Prince Hotel New Takanawa is gorgeous. It was designed by Togu Murano, but a craftsman named Yoshikawa made it possible. He realized all of Murano-san's design ideas. Murano-san also asked us to make a door handle for that project, at a similar level of complexity to that of the godlike work Yoshikawa-san was doing. *Laughs.* It required brass to be embedded in acrylic, an incredibly difficult process. In order to even attempt it we needed to learn many new techniques. But this in turn led us to new opportunities. Of course, I'm sure the conservative attitudes of modern manufacturers are partly responsible, but there are very few architects nowadays who make requests for new and interesting things like Murano-san did.

Architectural trends selected by society have become more and more generic. I'm certain it's because we're overflowing with things, approaching a post-scarcity society, and we can choose between a myriad of mass-produced options. I think that's why our creative intuition is declining.

Yes. Now nobody cares about details. Of course, it's impressive that architects are able to turn out so many buildings that meet all the modern requirements of compliance, low costs, and low risks.

But I heard they haven't even been selling well recently! Even though we architects have so many products to choose from, most aren't making the things that people really want. There seem to be fewer and fewer designs that really appeal to people. Because the general marketing philosophy is all about high volume sales, the designs come equipped with non-threatening mediocre functionality, and aesthetics that depict a shallow idea of universal beauty. There are fewer products on the market now that make people really say, “I want this!”. That is why I'm not pessimistic about people who have an ambitious mentality like yourself. Actually, I feel we are finally returning to a time where people demand quality, not volume and size. Just last month, for the first time in a while, I visited the famous wooden architectural masterpiece, Nara Hotel. I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to look around the back of the building. The way Tatsuno Kingo made Nara Hotel was very grand. But the details were so different from those of the New Takanawa Hotel's Hiten Main Banquet Hall!

Oh?

It's been there for over 100 years. Of course, it's in a great location. But it doesn't have so many fine details, so they feel comfortable simply replacing or patching over rotten parts of the foundation, or even covering them with some kind of cheap facade. I thought it would be better if repairs could be carried out in a way that respects the architecture, with methods more in line with history.

That’s a shame.

In the case of great architecture, if all the details down to the fittings and fixtures are made with artistry and care, then the buildings will remain relevant beyond their time, down through each generation who receives them. I am always truly impressed when I look at the fine details and quality of the parts in buildings by Junzo Sakakura and Togo Murano. Even if it costs a little money, I feel that when looking at it from a long-term perspective, it's better to build a great building with fine details that will be appreciated across generations.

These days there has been a huge influx of people from abroad who come to Japan to see Japanese architecture. Regardless of what period we are in, we still can't import and export entire buildings. We have to physically go and visit them, wherever they may be. If we fail to make better buildings, then people will stop coming to see Japanese architecture.

I really feel that way now. When I was a student, we were greatly influenced by the Dutch architectural movement led by Rem Koolhaas of OMA. He worked with Shohei Shigematsu, who we just did an interview with. People like Togo Murano represented modern Japanese architecture in a way that didn't place great emphasis on the decorative and fine technical details. They followed a much sleeker approach that was the heart of western architecture. But when I look back on Japanese history and culture, I think: Japanese people born in Japan are the ones building our buildings, so why wouldn't we investigate and include the finer details that make us Japanese?

Yes, true.

4. The Lasting Beauty of Quality Materials

People touch door handles more than anything else in a building.

Yes, they do.

Even just a slight change in their material can subtly influence our perceptions of a space, from soft to hard or cold to warm. When you really think about it, the material is the contact point between people and a building. And it has a way of elevating the quality of a building.

Yes, and handles are not something that really cost much money. Like you said, they are touched more than anything else in a building. Beyond the visual aspects of a building, touch can express a distinct quality and character. Recently, main entrance doors have become automatic. I think that's meaningless, like the revolving doors that are common in the U.S. now. Rather than cold steel bars that people push aside and pass through in one go, I wish more handles were created in ways designed to affect the way we feel when we move between spaces.

Yes, but now more and more buildings are using glass doors. Though, there is a movement to preserve cast iron and wooden doors, especially in Europe where hinges and mechanical rotary shaft fittings with automatic additions are popular. What looks like a big old church door will have automatic hinges and electrical assistance mechanisms. You push it just a little and it glides gently open! *Laughs.* I can never hide my surprise.

*Laughs.* Right? They make you pause and think, "wow!" The difference is that in Japan, automatic doors are taking over. With our tradition of sliding doors, the transition is too easy. In Europe, automatic doors still have a manual door opening mechanism. So many of their automatic doors still have a place for a door handle. Meaning they still have room for some character.

Japan has a long tradition of sliding doors from fusuma to shoji and sliding window-doors. The idea of just slapping motors on them feels pretty tasteless. Consciously using your hand on a recessed metal door handle gives sliding doors their character, along with the sound and the exertion of physical force. Automatic doors don't inspire feeling.

It's all because of the philosophy of "convenience comes first." We can't feel the character of the door; its movement produces no energy and no sound, only convenience. I want people to use real fittings and metal fixtures, not reinforced plastic imitations painted to look like the real thing. I think you know how good real fittings and fixtures are. The longer you use them, the more the characters and qualities of the materials stand out. The weight of iron, the subtlety of aluminum and the luster of brass.

Like you said, when the builder becomes the designer, they create whatever is easiest. You don't need good taste to turn a profit. That's fine for something like a porta potty, but buildings outlive people. When we chose materials, we ought to know their characteristics and carefully weigh their functionality for future generations.

Four years ago, I toured around Italy going to small fixtures and fittings factories. It really impressed me how they still used metal molds handed down for centuries. Techniques, too. Like how they would wait a certain amount of time after casting to finish the surfaces, letting the metal rest. They used skills handed down for hundreds of years, and they wanted to make things that would remain high quality for hundreds of years. In Japan products are sent to stores as soon as they are made *Laughs.* Of course, that's to be expected in Italy, a country that supports its crafts and architecture. I think this mentality is an amazing asset.

We talked about something like this last year at a restaurant in Milan where we were having dinner! *Laughs.* You said, “Like Italy, Japan has master craftsmen, but there just aren't enough people to continue the tradition! And what's worse, Europeans at least get to keep their old buildings. In Japan, we rebuild Ise Shrine every 20 years. Craftsmanship is all we've got!" After that you told me you were going to France to check on a project, and I told you I was going to do some research in Croatia for a lecture. In the end, I learned that in Europe, when they make cast fittings and fixtures, those fittings are made with the intention to last 1000 years. I learned the power of a cross-generational mindset.

That’s right. In Europe, crafted fittings and fixtures add historical character to buildings. The color of fittings isn't constant, they change with time, and we can enjoy watching how a building evolves with age. That’s what I wanted to talk to you about the most today, not just a rehash of Milan, of course. *Laughs.*

*Laughs.* Well, this is a continuation. I don't really have much interest any more in materials where the color and texture don't change. If possible, I would like my materials to transform in some way. Around that time, I was working on a project at your request for your nephew Teramura-san (Timber Dentistry, completed in 2014), and I used wood so that you could see the entire space changing with the passage of time. In terms of materials, let's say you're considering roofing. Your vision might call for slate, or copper panels, or older, more valuable materials. But nowadays, anything special costs a premium, so sometimes you have to settle for something that doesn't quite match what you envisioned. But for something like a door handle, you can make it perfect without spending a ton of money. I've been trying to incorporate elements like that in key places to highlight the living memory of the architecture through change over time.

That's pretty interesting. Next time let's meet in China, or maybe India. Oh, or actually, let's set it up so our next business trips take us to the U.S. together!

5. Self-Expectations and Achievements

What influence do you think your time studying abroad in London had on your way of thinking?

Studying in London greatly influenced me. It completely changed my values, ideas and approach to architecture. Ironically, Japanese university courses in architecture are essentially reflections of the construction industry, with the process of building at the heart of the curriculum. Rather than valuing creative thinking, they emphasize practical and efficient methods, teaching us how to work rather than think. There's very little philosophy. In other words, Japan taught me the importance of how something is made, and England taught me the importance of how something will be used. Of course, the school I went to was very liberal and I can't say that all of Europe or England is the same. But it gave me the chance to be taught the architectural process: not the simple goal of building something, but how to carefully think about the type of space, about how it will be used, and by whom. I was deeply impressed by this. It was so different from the way building is taught as the mission of an architect in Japan. For example, when making even a single building, we start by researching the area. We consider the influence we will have on the environment of that area over the next several decades, and how our building will change the landscape. Basically, we put together almost an urban planning proposal. And from there we try to pull out what we can. I learned how to decide on a plan that considers how the surrounding environment affects the people in it and the future development of an area. And I learned to never work in the so-called "economic style" of Japan, in which you decide on a plan simply based on money. *Laughs.*

Exactly. Rather than trying to maximize short-term profit, great architecture takes lasting value and future generations into account. So, I'd say your English education was actually practical, just on a longer and more meaningful scale. But it's surprising how different architectural training is in Japan versus abroad, how much more "practical" it is here. Surely anyone could see that it takes a knowledge of urban planning, travels around the world, and a sensitivity to culture to become a great architect, not just a mastery of construction techniques. Certainly, Tadao Ando is a case in point: powerful influences, vision, and experience matter a lot.

Ando-san is incomparable. He lived through such hard times and achieved such a level of mastery. Just having him here in Osaka is a source of great encouragement to us architects. I feel we have never had an architect as great as him, and probably never will again.

Yes. It all started for him when he saw a carpenter making a house.

Yes! He had an amazing power for grasping the simplicity embedded in complexity, even then.

Yeah. Incredible.

You have spearheaded UNION, a maker of doorknobs and fixtures, for most of your life. Do you see your passion for craftsmanship as underlying this?

I do. I love craftsmanship and I love design.

But it's nothing special.

No, no. I really admire all things you've done. Until recently, I only knew of your work with UNION. But you're the chairman of the Japan Building Materials Association, and you've built a whole community through the Rotary Club and your commitment to the UNION Foundation for Ergodesign Culture. So many people got to see the world of architecture through you.

Are you planning on many more trips abroad?

I’d like to travel a bit more.

Just before, I was thinking that I want to go to Italy. *Laughs.*

*Laughs.* You’ve travelled the world touring factories and design studios. Is there anything you've seen in natural environments, cityscapes, or architectural spaces that you think young people aiming to be architects should experience?

Mindset is everything. We send our employees to visit factories abroad, just for the experience. Some come back and say "It was amazing!" Some come back and say "Their craftsmanship can't hold a candle to ours, so I didn't learn anything. But I guess that's what you get when we're the best, right boss?" It amazes me how great a disparity we get in terms of how much people learn. In a sense I think you get what you ask for.

This may sound boastful, but I think our handles are the best in the world, in terms of design, materials, and manufacturing. History brings out beautiful principles and correct ways of doing things. It also gives you the attitude you need to see the world.

Yes, yes. That makes sense.

If you ambitiously follow your heart, that passion will help you see new perspectives overseas that you'll be able to take back with you.

That’s what I think. When you went to England you were very motivated. You expected a lot from yourself and I feel you really got something out of the experience. When I ask our employees, “How was it compared to UNION?,” they just say that UNION is better. Maybe it’s because of the familiar values they hold. More than anything else, I think intellectual curiosity and following your heart will broaden your perspective. I think you learned so much because you were always trying to acquire new knowledge and wisdom. There's a huge difference between, people who just go abroad and those who go with expectations of themselves. The world-famous Kei Nishikori became so good because of the expectations he held for himself. I hear fewer and fewer students are going abroad with this mentality. But I want to them to become people who grow and then come back home, like you did. *Laughs.*

I can't even remember what I was like back then anymore. *Laughs.* I hope I can keep learning, though.

6. Structure, Design and Innovation for the Coming Generation

You know, recently I think people that can create things from scratch have become incredibly rare. It doesn't matter whether we're talking about door handles or architecture. Take locks, for example. Ever since shoji and fusuma sliding doors became popular in most houses during the Edo period they've been the standard. You always used to lock them with special wooden bars, called shinbaribo. Even today, they use them at the great shrine in Ise, and in old storehouses. We even used to have special bolts for sliding shutters. Modern cylinder locks and keys were developed in France under Louis XVI, and became popularized through the United States in the early 20th century. In Japan they were mastered and improved by the good people at Miwa Locks, who introduced a number of innovations. Door handles are the same: they didn't used to exist in Japan. But unlike locks, there wasn't a single company in the world specializing in door handles. Then we came along, and we've been continually innovating and improving their craftsmanship and design. That's why today we have almost 3000 different kinds, and that's why we're the best at what we do. *Laughs.*

That’s a great achievement. It’s the result of the intellectual curiosity and motivation we were discussing before. Ideas lead to discoveries, discoveries to development. It’s inspiring.

Without learning from our history and using our own originality, we would only ever produce copies and criticism.

Even now, there aren't many manufacturers that make handles exclusively, right?

I haven't found another anywhere in the world.

Because of UNION, I was sure that there would be others.

None! Huh. *Laughs.*

That's why the world likes our products. *Laughs.*

Whether through companies like ours or not, what we need is more young people going out into the world. Travelling has become easier, and Japan is now a small place. I wonder what will become of architecture in the future.

I'd like to see people boldly taking on innovative new challenges and doggedly persevering.

And at the same time, it's our duty to preserve historical buildings to pass them on to the next generation.

It is indeed.

A single dominant, unipolar solution is rarely enough anymore. We've entered the age of multipolarity, diversity, and evolution, where this generation will need to find efficient, elegant and shareable solutions tailored to all kinds of different problems. It's like bringing in relief pitchers in baseball.

Hahaha. *Laughs.* Yes.

I wonder if we can connect to the younger generation in a positive way.

You're still young! You're just in your mid 40s, right?

I guess, that’s true.

If there's a need for mentorship and a place for me, I'd be happy to play that role for young people. *Laughs.*

*Laughs.* You'd better do that. I think it's the same with everything. Knowing the value of Japanese architecture makes it possible to interpret and make use of the good aspects of different cultures and civilizations. That’s important. People who can preserve and develop those ideas become cultural links in history.

Yeah.

There are so many great aspects to Japanese architecture. Even just from the perspective of the Japanese climate and natural environment, our wooden buildings have many good points. But they are vulnerable to natural disasters like earthquakes and typhoons. Solving these problems gives us the potential for exciting future architectural developments.

Exactly. You've spent so much time interacting with architects that you've practically become an expert architect yourself! *Laughs.*

No, no. It's just words. I can't draw up plans or anything like that, I can just tell if a building is good or not. But it's been interesting for me. I've been feeling the need to research new fittings for wooden buildings that harmonize with changes in the earth's crust.

The current system of wooden construction is old. Our own "Zairai" post and beam construction technique comes from simplifying and developing traditional methods of wooden construction, which themselves had been evolving since ancient times. It came into use about 50 years ago and was considered the standard. Now a hybrid of the "Zairai" method in combination with load bearing walls has become mainstream. Recently, natural disasters like earthquakes in major urban areas have affected many people's homes. Towards the end of the Showa period, the use of metal reinforcements became mandatory. But they are quite large, and often result in the traditional joinery and beautiful details crafted by master carpenters, being hidden away. If these reinforcements become an essential part of the aesthetic, then Japanese wooden construction would become even more prominent.

That's right. Just like the earthquake-proofing of current schools and public buildings with cross-bracings that look like monsters clinging to a building. If reinforcement is the only goal, then you will get some really bizarre looking things.

Yes, they can be pretty grotesque. *Laughs.* Of course it's important to guarantee safety. I think drawing up plans with an earthquake resistant structure that increases the quality of the space itself motivates more people to seriously consider it. Designs where you can see seismic resistance calculations on a plan, but not in the finished structure... It’s a shame this hasn't been written into the earthquake resistance standards. As with money, there's no limit to safety, but I would like to see people attempting to design reinforcements that create a new sense of value.

We need to think about it more.

Yes, maybe things would change if a manufacturer like UNION with a keen sense for refined detail made seismic metal reinforcements.

I've actually been looking into earthquake resistance. *Laughs.* This building will be 50 years old soon, so I wanted to bring it closer to the current earthquake resistance standards. We researched it with the idea that if we could make them in-house experimentally, then they could be manufactured in a way that wasn't embarrassing to look at. Imagine a beautiful design complimented by the reinforcement functionality of the fittings and fixtures.

I felt that undertaking this challenge could motivate our staff.

I'm sure it'd boost staff morale, and I think we are moving towards an age where there will be a high demand placed on metal fixture manufacturers.

For example, when making a separate order for structural fixtures, architects will specify in their plans the craftsman who should be in charge of the work, categorized by construction types. A blacksmith will make things that are rustic and rough, a metal fitting maker will create fine, beautifully finished fittings. Wood will have to be handled a bit differently. I envision ordering through a carpenter who deals with structural materials or decorative items, from a wooden relief craftsman, and so on. This system would rely more on the power of people than the scale and accuracy of mass production. It shouldn't be too difficult to do for companies such as UNION, that follow a tradition of masterful craftsmanship.

Absolutely. Wooden buildings especially have so much depth.

Yes. I think that demand has increased, and it will continue to grow. Especially with large scale buildings, like the National Arena, there are limits to the lengths and thicknesses of materials. The burden of making something structurally sound that relies only on the load tolerances of base materials would be too great, not to mention shipping costs. When considering methods to disperse the horizontal forces generated by earthquakes and storms, we inevitably realize that metal reinforcements are needed.

Right. I think they need to work in harmony with the design.

There's a relationship between base materials and metal reinforcements. Rather than supporting one or the other, I want to create a design where they're mutually supported by, and support one another.

We have to think about that.

Recently, earthquakes across Japan have created a need for lighter buildings. Buildings' earthquake vulnerability is equal to the square of their weight, all else equal. That’s why the move away from paper-mache architecture to structural designs will become mainstream. Tiles and stone used just to finish walls only weaken buildings: walls have to be made as light as possible. Otherwise, structural engineers get called in to make calculations for necessary metal reinforcements, which end up looking quite out of place. *Laughs.* It’s not my area of expertise, but if I could work together with somebody like you, a designer who understands structure, we might be able to make something happen.

Yes. And you know, an understanding of space is as important as an understanding of materials in good structural design.

That’s right.

Nothing should look out of place.

And I think reinforcements should be something becomes important to us, because they keep us safe.

Yes, that's why I want a manufacturer like UNION to do the hard work and get something out there for the world of architecture. *Laughs.* I really think it can work.

7. A Wide View for the Global Market

You help organize U35 [Under-35]. What motivates you there?

The event was first held in 2010. The year before that, around 2009, magazines and books like SD and Architecture Culture were gradually discontinued, and architectural media began to disappear. I became independent in 1999. At first I wondered if I was all alone in the world. *Laughs.* I finished my first work, “Time and Space House” in 2000. I worried that the next generation of independent Japanese architects, who would come along in 10 years or so, wouldn't have anywhere to present their works. The 4th generation of Japanese architects and firms, such as Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa's SANAA, Kengo Kuma and Shigeru Ban, who are now greatly successful, had started to gain international recognition around 2008. Each generation of Japanese architects has found acclaim overseas, including the first generation of Kenzo Tange and Junzo Sakakura; the second generation of Arata Isozaki, Yoshio Taniguchi and Fumihiko Maki; and the third generation with Tadao Ando and Toyo Ito. Many of my generation of architects studied abroad and learned how well regarded Japanese architects actually are. Sometimes I wonder if we aren't even a bit overrated. *Laughs.* But I asked European architectural writers and critics about this. I heard all sorts of opinions, but ultimately, everyone said it has something to do with Japanese architects becoming independent early in their careers.

That’s true in comparison to Europe.

The evaluation criteria of architecture have remained the same, with Europe in the center. It's time for Japanese architecture to represent Asia, but that message isn't being heard.

In Europe, on average "young" architects become independent around 40. It’s interesting to analyze the reason. The history of European architecture is based on buildings that will stand for 1000 years, while the essence of Japanese architecture is represented by Ise Shrine, which is rebuilt once every 20 years. Our tradition passes along craftsmanship and techniques. Repeatedly tearing things down and rebuilding sometimes has a bad image in the Japanese construction industry, but it's resulted in a tradition of continuously developing technology and nurturing new craftsmen. For architects like those of my generation who become independent in their twenties and early thirties, it’s equivalent to being jobless, to going into isolation outside the framework of accepted society. But from there we can start accumulating experience, with small jobs like renovating houses, and in this way, we start our training early. Japanese architects become independent early and take on small jobs like restoration projects. Then historically we've used architectural media to present our works, which provides a way to let the established architects know we exist.

From the new Louvre Museum building in France [design: SANAA] to the rebuilt WTC in New York [design: Fumihiko Tsuji] and the world's largest opera house in Taiwan [design: Toyo Ito], Japanese architects play a role in most of the world’s important buildings today. I think there's a real path forward to the international stage. It's not easy, it's a steep and challenging path, but people make it. And to advance, young architects have to avoid working for conglomerate design firms or design departments at large general contractors. They have to strike out on their own, contribute to society, and build their skills, endurance, and personal brand. But with the decline of domestic architectural media, people lose a crucial forum in which to present their works, losing a major motivational goal. Of course, architects don’t create a building just to show it off, but without a place to promote their work they lose hope that it will connect to something new. I think because of a culmination of things like that, the number of architects becoming independent has dropped drastically; they are opting to work for the conglomerate design firms and large general contractors. I guess in modern society, after people are in their mid-30s, they have to take on many social responsibilities: family time cuts in to work time.

Maybe it depends on your age, but having a family can restrict your financial freedom. People develop a more conservative idea of stability. Ultimately, many have to give up on their desire to go independent. They can't take the risks they would have to pursue their true goals.

When I was young, I didn't think about those things at all, I was just optimistic. Life felt like a board game where I was optimistic and happy to follow the roll of the dice. *Laughs.* But anyway, after considering the situation in Japan and the opinions from abroad, I decided to create a place that was like a real life exhibition, a sort of entrance gate to the architectural world, providing up-and-coming architects a place to present their works. First, I asked some successful architects of a similar generation, such as Sosuke Fujimoto, Junya Ishigami, and Taro Igarashi, to get on board. Then I went to some architects from the previous generation and some architectural critics. Then I consulted Toyo Ito, who was the biggest name in the construction world at the time, and he gave me his support, saying, "It's a good idea, let’s do it together." And the event is still going strong, and we're always taking new applicants!

I see. Because of your wide perspective and ability to see things from many angles you can get a lot of people on board with your cause.

There's a group called the Building Materials Association, which used to be mainly made up of companies dealing with structural materials: window sashes, glass and cement. It used to be a big group. Then, it was divided into smaller groups that broke off, and now the BMA is made up of a small group of those who stayed behind. We're still part of that group as a metal fixtures manufacturer. They have some finishers, and a bunch of small-scale manufacturers. So... the group is not that internationally oriented anymore. But I think that's dangerous. It will be difficult to survive in the future on domestic demand alone. With Japan's declining population, we know that our numbers can only decrease. If possible, I want to make people look abroad, maybe even form an alliance-like group. There are many difficult aspects of going abroad alone, so I want to work to form a team like that. I feel now is the time to make the most of our technology on the world stage. And after talking with you, I think we see eye to eye, so thank you.

No, not at all. This U-35 is still only in its eighth year. I have to try to keep it going for at least 10 years. But I don't have enough experience with this sort of thing to know how things are going to develop. *Laughs.*

What you're continuing to do is amazing. It creates deep trust within the community.

But still, if young architects don't go abroad, they won't be able to find work. You're almost never in Osaka.

No. There's nothing domestic. *Laughs.*

70% of the job requests my office gets are international. More than 80% of the design competitions we enter are for overseas too. And the domestic requests we do get are not the kind of large-scale projects international architects usually deal with, but small renovations and single buildings with tight budgets. Globalization means that people can choose services from across the world regardless of country. We get many requests for consultation because of the Japanese reputation for quality.

My office is located two blocks south of UNION, actually. *Laughs.* I'm in Osaka for a third of the month, and another third is in other places in Japan, like Tokyo. The remaining third I spend abroad.

So, does that mean there's no real reason for you to be in Osaka? *Laughs.*

Yeah. *Laughs.* I only have one project in Osaka, doing some area planning in Shinsaibashi. In the whole Kansai region, I typically only have about three projects across Kyoto, Hyogo and Wakayama. I'm always working away from home, mostly in Tokyo or overseas. Osaka is just part of my image. *Laughs.*

Unlike fashion, consumer products, or graphic design, you can't ship out your architecture, so in the end we architects have to show up at building sites. Architecture firms can become almost like think-tanks, so caught up in ideas. We assume that our designs will actually be built a few years down the road, but it's great when we can see our designs become actual buildings. Architects talk and think so much that we can lose sight of whether the building was ever actually built. We already finished it in our minds and on the proposal we submitted. *Laughs.* That’s why it's nice to live somewhere where I can feel the day to day reality of life. I was born in Osaka and raised in Kyoto and Tokyo. However, I went to university in Osaka and London, and my first job was in Osaka. And because of that connection, my office is still here. But if I had no connection to Osaka, I would have moved the office already. And then, I also stay because of people like you, without whom I would probably be somewhere else.

No, no. You don't need my support. *Laughs.*

That’s not true. In the end, I think I'm who I am because of the people who support me.

Even if they were at times quite harsh or even scary. *Laughs.* Part of why we stay places is because we have a support network.

Maybe it sounds self-centered to talk all about where I get my support, but I believe that world-renowned architects should support their home communities. I'm weak-willed, and so if I had been born and raised somewhere else, amidst different people, I think I would have abandoned my design dreams as delusions of grandeur. The rest of the world would be out of reach. I would be working an ordinary job at a construction company or a design office in the city, with my main goal being to provide for my family. For whatever reason, so many architects have ended up having relationships with Osaka, from Tadao Ando, Togo Murano, Setsu Watanabe, Kenzo Tange and Tatsuno Kingo. These heroes inspire and motivate me, and their characters and sensibilities are rooted here in Osaka.

There's something about Osaka. In terms of the rest of Kansai, I can't say Hyogo or Wakayama have produced many architects. Kyoto has...

Kyoto has... Kiyoshi Seike is known globally, right? I can't remember anyone else.

Our national media, economics, politics, and educational institutions are all concentrated in Tokyo. It has almost become the duty of those born and raised in rural areas to attend university in Tokyo. Even students who excel in Kansai find employment at Tokyo companies. So in the near future I think that most Japanese architects will come from Tokyo. But, well, I don't think it's numbers that make amazing people like Tadao Ando appear, so there’s nothing I can say. *Laughs.*

I see.

Still, there were so many architects all over Japan in the old days. Now, their numbers have dropped by more than half. Maybe more?

I don't know how many are actually working in design, but in recent years, the transition from handwritten drawings to CAD has changed designers' mindsets. The government's reduction of wasteful spending on unneeded public construction projects, and the fallout from large scale scams by major construction companies like the Aneha controversy, led to a drastic improvement of the Architectural regulations. In a good sense, useless projects were canned. Even with that, I hear that there are now over 1 million certified architects. Among them, some work checking proposal applications, or in administrative agencies, or in sales and general affairs for conglomerate house makers. I hear that only about 30,000 people, or about 3%, are actually involved in design. Recently I heard from Sano-san, the chairman of the Japan Architecture Office Association, that the number was 100,000 in 2008, so it's actually down to about a third compared to the recent past.

Really? Of those, how many architects specialize in Japanese architecture? 100 or so?

The Architecture Lecture Series I mentioned to you earlier will be held for the 50th time this year. If you count all the architects who came as guests, even including the younger people, there's no more than 100.

I see. Perhaps in 10 to 20 years our building materials industry will follow a similar downward trend. In that sense, we have to look beyond the domestic market. Only companies that successfully go global will continue to develop. Or well-established stores that can survive on a small scale. I think it's one or the other.

Yes, that's true. If you limit your market to a certain area, then you'll end up only making products to meet the demands of that area. It also limits your opportunities to learn as a designer. Hearing opinions from the widest possible range of cultures and lifestyles is how you get new ideas.

That's right. I think we need to take advantage of the history of fittings and fixtures to introduce new functions and ideas. It's pointless trying to push products developed solely for the Japanese market. But adapting and developing products that incorporate Japanese crafts and traditions for a wider market would likely be well received.

Japan’s climate is hot and humid, with dramatic climate changes between the four seasons. So manufacturing techniques have adapted and progressed. We learn from ancient innovations that remain preserved in traditional methods of craftsmanship. That's part of why we have such distinct regional characteristics, and that gives us a toolbox to adapt to the world stage. For example, when redesigning something like this [door handle] for the cold climate of Northern Europe, we have to take into account the climate and natural environment when considering how temperature will be transmitted through the grip... We can draw on our traditional regional intuitions.

Yes, that reminds me of a story from when I was younger. Back then, if you touched a normal door handle in Hokkaido, your fingers would stick to it. So Hokkaido-specific handles we manufactured with a special finishing material to adjust for the temperature difference with Honshu. Now, finishing materials with high heat transfer rates are no longer used, so it isn't something we need to think about anymore. But at that time, you had to design products to match the climate and natural environment. Even now, when taking Japanese products overseas, it’s important to consider the climate and environment of your destination.

I agree. We can prove how great Japanese technology is. Of course, being recognized abroad is important, but at this age I'm coming to feel again how tenacious Japanese people are. People of your generation have something that is deep and special. We have to pass it on! I finally realized this at 45.

No, no, there’s no need for that. Maybe what I really want to see is more younger people with the grit and determination to be active overseas. You used to see Japanese people doing things anywhere you went, but now wherever you go there are only Chinese and Koreans.

It’s true.

I want young people to fearlessly head out and explore!

8. What the UNION Foundation of Ergodesign Culture Achieved

It's been about 20 years since you started the UNION Foundation of Ergodesign Culture, right?

Yeah, 22 or 23 years.

Was there some special purpose that led you to start the foundation?

A purpose… *Laughs.* No, no, there wasn't any noble goal.

But you’ve continued it for over 20 years, that’s incredible!

That was a time when the Japanese economy was getting worse.

You made a foundation at a time when things looked pretty grim.

Yeah, I started it when the economy was bad because I felt compelled to give young architects a chance.

When I was young, I spoke with Keizo Saji of Suntory. He said when the economy goes up of course it’s a chance to make money, but when it goes down there's a chance to guide the next era: to leave behind a legacy.

That's absolutely true. And I'm glad that I've been doing that.

So why did you start out giving international grants?

By giving overseas subsidies as well as domestic ones, I thought it would open up new opportunities for the applicants. Back then more young people, including you, went overseas. From studying to researching, or even presenting research, everything costs money. So I felt that I wanted to do something to help.

There are still plenty of domestic designers who haven't applied for or been involved in the grant program, so it has room to grow. But there are lot of people like me who have been fortunate enough to receive the grant. And then, it's touched so many people, including the more senior architects who get involved as judges.

Yes. We get about 250 applicants each year for our design awards and research grants. Though somewhat more people apply for the design grant.

That's great! For 23 years! You must have made an impact on a huge number of people!

It makes me happy to hear it put like that. Some people tried and failed, but then continued to try again and again. They're all outstanding people.

*Laughs.* You have one of the most humble and respectful personalities of anybody I've had the pleasure of meeting. People in the academic world don't really know building material makers, usually. Perhaps the UNION Foundation of Ergodesign Culture could be a gateway to more people knowing about UNION.

That's definitely a possibility. Who would have guessed that so many famous architects such as yourself would participate in our small business initiative? I'm so grateful to everyone who has worked with UNION so far to make this all possible. Normally, no one would give a company like ours the time of day, let alone meet with us. *Laughs.* Even now I can't believe it.

Of course, a big reason is this foundation. When my sales staff bring catalogs to architectural firms, the architects make time to meet with them. I hear they don't usually do that for salesmen from other building manufacturers. My predecessor always used to tell me that it's important to give everything your best effort since you never know what might come of it; quality work pays for itself in the end. He was full of great lines like that: "Handles are the face of architecture. They're the first part of the building we touch."

I've known you since I was young, and I'm certain your uniquely wonderful personality has made UNION what it is today. Do you have any more stories like that about your mentor, who helped shape you?

I used to talk with him about how TOTO's washlets and bathroom equipment is all branded with the TOTO logo. We decided to put a logo on our handles. He and I decided that if there was a UNION logo on all our products then we would have a certain responsibility as employees. And then, people who used the handles might start to wonder "What kind of company is UNION?" If we made a bad product, it would be a logo for complaints. For better or for worse, we would be responsible and could possibly receive praise or admiration.

In our profession, saying something is "Designed by _______" is a real marker of responsibility.

9. Conceptual Products that Cross Borders

How have UNION handles been received abroad? I'd love to know how you've expanded globally, and where you're going from here.

I wonder how many years it's been since I started going abroad?

Long ago, when I started out selling abroad, I would speak the most terrible English. Like some Osaka street language. *Laughs.*

*Laughs.* You know, you're kind of like Tadao Ando from the architectural world. No matter where you go, you talk like an Osakan, but somehow you communicate more effectively than those who speak fluent English without your spirit.

Maybe not that well. That was about 30 years ago. Even back then I knew we had to start selling globally. I think more than just running a company, we have to grow it. Even if it's just by a few percent, it energizes the company and gives us the opportunity to try new things

Any job has its hard parts. But when people love what they do, that enjoyment is expressed in their products.

Yes, that's it.

When you look at what we make, do you think there’s anything we could do to improve?

Please let me know if there's anything that you think we could add or improve to appeal to people abroad.

I have absolutely no understanding of or experience in sales; I can only give you my entirely unprofessional opinion. *Laughs.*

In Japan, designers are often told to avoid doing anything too strange. But sometimes, strange can be good. It's almost a sense of exoticism. Especially for overseas projects and proposals, if people have a real sense of where the architect is from and what his or her roots are, it's easier to connect. In places with a lot of immigration like Europe and America this is true even more so; people want to know your background. Since we're coming all the way from the far east, I think it's good to let people know we're Japanese, and to say "this is a Japanese design."

I think in aspects of our daily lives there are many deeply Japanese things so ingrained that we don't even notice them. Layers of meaning are imbedded in our geology and our geography as an island nation. Our famous hospitality is in some ways an offshoot of a deeply homogeneous society. You can get an idea about what makes Japan special by asking people in other countries, but those answers tend to lack historical or cultural context; they're sometimes even comical. So I think the ideal is for a Japanese designer such as yourself to travel the world and grasp the essential value of Japan from within and from outside.

When foreign manufacturers try to make products tailor-made for the Japanese market, the results are often pretty bad. I think it's better to just come out and say, for example, "Made in Germany!" Make it a selling point. The cultural, lifestyle and traditions of Germany gives German products a certain intrinsic value, and people want them for what they are. I try to create and market value in the same way, without hiding our Japanese-ness.

It's been about 20 years since I first heard talk of globalization. In Japan, we need to stop worrying "is this Western culture? Is this Japanese? Maybe this has pan-Asian elements?" We're moving towards a fusion. And we should create things by focusing on the familiar details we find in our own surroundings, communicating basic processes to reconceptualize the familiar. I think that's an important part of expressing the appeal of Japanese products to people abroad.

That makes sense. Processes...

I want to position us with that kind of Japanese branding, and to promote it for companies more broadly. A little like how Japanese hospitality has become a global brand.

Yes, I think that's a good idea.

I think that's the way to get our products to take root overseas. More specifically I want to do a really visual display in the form of an exhibition. And it has to be inextricably linked to architecture and the role of buildings in shaping our daily lives. The Tokyo Olympics and Expo '70 helped put Japan on the map. They helped us gain credibility. But now we need to put together something that will represent our industrial and manufacturing culture, and then to bring that to the world.

I agree. Typically, well-established companies don't display their existing products at exhibitions. They usually show concept models to express their future direction.

That’s right.

It started with companies displaying concept cars at motor shows. For simple types like me, it shows us the amazing possibilities of the future, and we think, “What a great company!” I'm pretty easily sucked in and impressed. *Laughs.* I think we truly feel something close to the enjoyment of their creators. But in Japan, European cars used to be imported as-is. Take left-hand-drive cars. Even though we drive on the right, the people of this island country began to yearn to have something that was different. We came to respect that difference.

Ah, right.

When I was a kid, everyone wanted one. Of course, they don't really meet Japanese regulations and safety standards so they're rare now, but that kind of easy-to-understand differentiation creates a sense of identity. Even when cars are tailored to Japan with cutting-edge market research and fitted with all the latest accessories, they still doesn’t create the same sense of value. The difference between a European and a Japanese car becomes less tangible, and people lose interest.

I hope that cars in Japan won't end up all the same. I love models with distinct individual qualities and diverse designs and functions. The world is already connected through IT, logistics, and advanced transportation. Globalization has happened and countries and regions no longer compete with one another. Instead, difference just becomes differentiation, so it's great that each country has its own unique qualities. And it's good to have representatives who advocate for their countries. But at the same time, we need a place where we can properly explain our values, somewhere everyone can find recognition and respect, with maybe like a President of Earth. *Laughs.* It’s time to create an organization whose representatives advocate for and protect the world as a whole. Then, I hope local manufacturing industries can redevelop their unique characteristics.

Yes, even though we're a small company, I want to take on some big challenges with that kind of desire and passion.

*Interview concludes*

Thank you very much.

Planning: Naoyuki Miyamoto, Keigo Kuwano

Photography: Norinao Miyanishi

Reporting and writing: Yoko Ikegami